Reclaiming medium sized towns

Urban centers and how the suburbs made nonurban living unattractive

I was walking the streets of Brooklyn on my way to work one morning, and it was a particularly windy day. A cloud of glassy dust blew into my face. I immediately shut my eyes; they burned as the particles irritated them. Huh, I thought, I wonder if this is why Thoreau went to live out by a pond.

I just spent a couple of days on Jekyll Island in southern Georgia. Not a bad spot. It’s full of late-19th-century architecture built by the likes of the Rockefellers, Morgans, and other bigwigs of the Gilded Age. This was probably too remote for most people to live their industrious lives, but it certainly gave them space to retreat.

In the 1790s, coastal cities in the United States were a far cry from the rapid population growth that accompanied industrialization in the 19th century. For years, city streets didn’t even have names. They were home to livestock and functioned as blurry, halfway zones, somewhere between rural countryside and what we’d now recognize as a small town.

Compare that to our French or British counterparts. London and Paris were immediately identifiable epicenters of their nations’ wealth and power. In the early U.S., cities like Boston, New York, Richmond, and Charleston were still coterminous with the rural. They weren’t distinct in the way European capitals were.

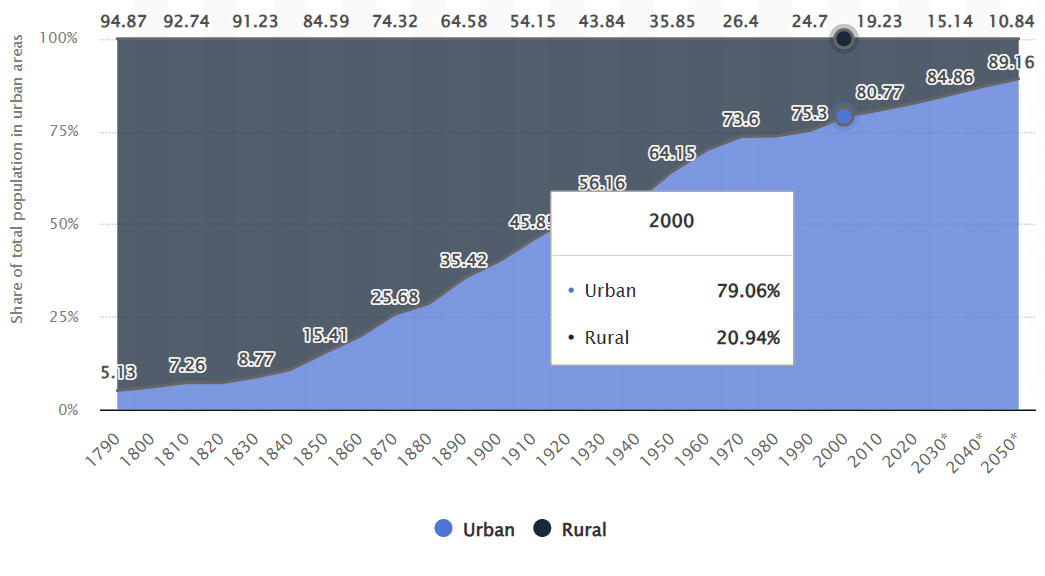

Here’s the data (and forecast based on current trends) for how many Americans will live in urban centers over the next twenty-five years:

Medium- and small-sized cities continue to struggle in the face of the exodus to major metropolitan areas. What usually happens is this: the jobs move to the urban core—think Dallas—and then the outlying “cities” become bedroom suburbs of the hub. That gives us the kind of bloated suburban design America is infamous for.

However, medium-sized cities could adopt a distinct aesthetic.

Look at some examples in Europe. Take Perpignan, France, which is not even a major tourist destination.

OK, sure, it’s a well-lit photo, which helps. However, I would like to draw your attention to a couple of points. First: density of housing. Americans love their square footage. They think they’re getting comfort in return. I no longer buy it, even though I once did. The middle-class aspiration for a large footprint was a postwar invention, a product of undeveloped land and car ownership.

There are three issues with the suburbs that, in my view, are insurmountable as long as their current design remains unchanged. Purely residential suburbs lack:

Aesthetic value

Spontaneous social opportunity

Transportation options that are green and safe

These aren’t just idealistic values. They’re practical ones that can’t be served by profit-driven development alone.

But before you roll your eyes at those three values, ask yourself whether you already honor at least one of them in your life. Take food, for instance. You could eat Soylent three meals a day, alone at your desk, without caring about flavor, aesthetics, or company. But you probably don’t, and it’s good that you don’t.

Here’s Roosendaal, The Netherlands. It’s nice for exactly the three reasons above.

For anyone living in a major urban center like New York, Los Angeles, or Chicago, it may be time to consider reclaiming America’s medium-sized cities seriously. Much like legislation, once we build something, it’s tough to undo it. Suburban housing developments next to strip malls are investments that will outlive us.

The only real hope we have against bad urban planning is to create better new projects. The idea that we’ll significantly restructure the existing housing stock is flawed for two reasons. First, we aim to preserve existing housing to maintain low real estate prices. Second, demolition and rebuilding would be exorbitantly expensive.

This calls for some bold conversations.

Under my account, it’s perfectly valid to tell developers—or city officials—that their plans are bad because (a) they’re ugly, (b) they don’t allow for spontaneous human connection, and (c) they are too car-dependent. Those are real criticisms, especially if you’ve seen buildings with windowless apartments, no grass or trees, and designs that feel like they were spit out by an algorithm.

You may not be able to recreate Berlin’s architecture in suburban Texas. But you can stop pretending that what we’re building is good urbanism just because it’s spacious.