ego-death and how spinoza doesn’t seem to care (but I care)

sartre's pretty technical. at least he doesn't downplay annihilation.

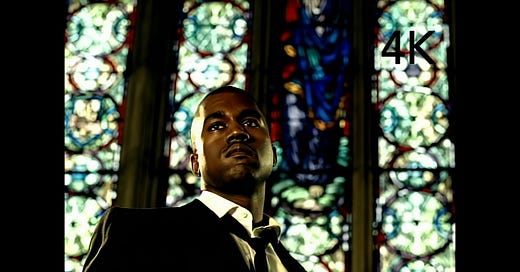

"I wanna talk to God, but I’m afraid ’cause we ain’t spoke in so long."

— Ye, “Jesus Walks” (2004) back when Kanye West had his mind intact and wasn’t showing pornography to Adidas employees designing his shoes.

I started thinking seriously about God years ago. I’d been a lifelong Episcopalian, and I still go to church on occasion—mainly because it’s the only place I know where you can sit in an old building in silence, smell hot candle wax, and listen to people who think hard about the shape of the universe and its relationship to justice, mercy, and the sheer bizarreness of being a conscious being in an otherwise unconscious world. Show me a psychoanalytic institute that offers the same ambiance, and I’ll start going there instead.

Spinoza is one of the quintessential believers in a rational God. What’s the difference between rational and irrational gods? It’s not rocket science. The rational God is as he has always been: silent, embedded in the physical laws that govern reality, an ordering principle rather than a personality. He holds the actual infinite set of natural numbers. He’s the unmoved mover—the quiet boss.

The irrational God is far more intimate. He’s the one who appears in burning bushes, speaks to Kierkegaard in stories about chopping off your son’s head (sorry, Isaac), and makes his adherents babble in tongues to prove their divine status. I keep watching William Lane Craig debates, waiting for him to bridge the apologist gap between the rational, intellectually compelling Spinozist God and the Biblical, irrational one. Alas, I think it cannot be done.

During the 17th century, before Christianity’s familiar orthodoxies hardened, heresies were everywhere, endorsed by some of the best minds. When confronted with doctrines like Trinitarianism, which insists we can fit a square peg into a round hole because of holy mystery, there used to be plenty of off-ramps for those unwilling to suspend too much reason. John Milton, for example, was an Arian—he believed Jesus was not consubstantial with the Father, not the same being, meaning he rejected the Nicene Creed, the most orthodox thing you can believe in 2025. C.S. Lewis was so disturbed by Milton’s potential heresy that he misattributed orthodoxy to him.

Spinoza’s God can be called upon in times of spiritual need, but only in quiet contemplation, never in the clenched-hands desperation of a foxhole prayer. In crisis, you’re meant to think about the elegance of geometry, to console yourself that your soul can comprehend it. That might be fine (if it worked), but it remains deeply unsatisfying in the face of mortality. Spinoza, like the Stoics before him, claims the fear of death is born from ego-preservation, but these guys were so unbothered by ego-annihilation that I doubt they ever really considered it.

In Being and Nothingness, Sartre describes death as the triumph of the Other over us. He argues that death "can only remove all meaning from life.” If anything, the irrational God—the one who consoles in embodied flesh—is far better company in the face of death than the God who lets egos dissolve into nothingness. In this sense, Kierkegaard’s relevance lies in recognizing our psychological need for salvation from oblivion, a need most Christian traditions promise to fulfill. Some do so more crassly than others—like the ones that assure me I’ll be reunited with my dog in the afterlife. Boy, wouldn’t that be cool.

In America, secularism is needed nationally, while religion is needed locally. You should be going to your neighborhood synagogue, mosque, or church to talk about the afterlife—that’s part of the deal of being human, hashing these things out together. But letting the superstitious dictate public policy is untenable. That’s a tough split. It’s better to take a walk in your neighborhood, step into a local place of worship, and wrestle with these questions alongside others than to sit alone at home, stewing in existential dread and hating the wackos in Congress. You have to choose where to be loud and where to be quiet.

Works mentioned in this post

I would never recommend “Being and Nothingness” by Sartre. It’s big, technical, and frankly, a lot of it is gibberish. But if you’re keen, I would recommend the SEP entry on him.

I wholeheartedly recommend Steven Nadler’s “Ethics: An Introduction.” Amazon has some 30 buck copies if you want your own.